In continuation of the discussion on the exercise of ecclesiastical authority, today’s post focuses on the phenomenon of sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults among Church personnel—a manifestation of abuse of authority.

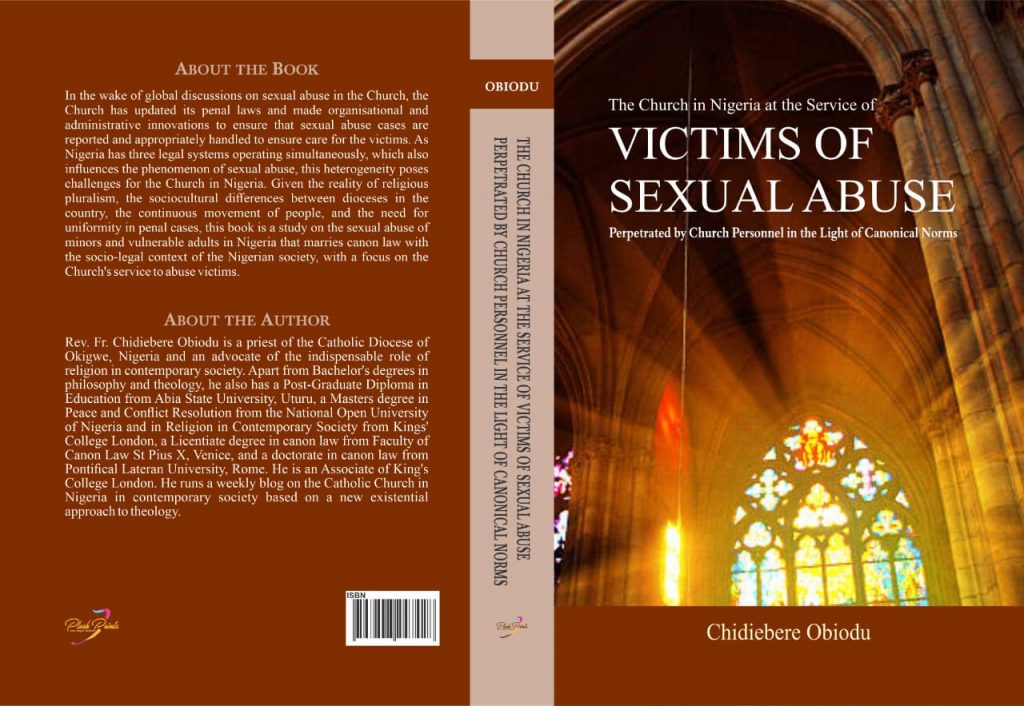

In this post, I wish to introduce my book titled: “The Church in Nigeria at the Service of Victims of Sexual Abuse Perpetrated by Church Personnel in the Light of Canonical Norms.” Church personnel here means clerics, male and female members of institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life, and lay persons who enjoy a dignity or perform an office or function in the Church (Can. 1398).

This book, a product of my doctorate research in canon law at the Pontifical Lateran University, Rome, was first published in November 2022 and updated in September 2023 to reflect Pope Francis’s latest changes regarding reporting sexual abuse cases. Rev. Prof. Davide Cito, a professor of penal law, the Vice Rector of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross (Santa Croce), Rome, and a consultor to three Roman curia dicasteries, wrote the preface to this second edition. Today’s post is a review of the book.

Nigeria practices legal pluralism, that is, having more than one legal system operating simultaneously within its territory. These legal systems are English law, customary law, and Islamic law. Given this complex mixture of laws operating simultaneously within the same country, it is sometimes unclear about the law applicable to a given situation. Nevertheless, a fundamental yardstick is that English law, the constitution, and the enacted statutes by the parliament across the thirty-six states and the FCT apply to all Nigerians as public law. However, people can choose any law to regulate their conduct regarding personal matters.

The laws of each legal system can sometimes differ substantially. For instance, while the Child Rights Act (English law legal system) stipulates that one becomes an adult upon reaching the age of eighteen, Islamic law teaches that one comes of age at puberty. Besides, while the concept of a “vulnerable adult” is in Nigerian laws, the concept of “one to whom the law recognises equal protection” described in canon law does not exist in them.

Since there are discrepancies among these legal systems regarding behavioural norms and child rights, there are many challenges in having unified civil legislation in Nigeria on the sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults. These discrepancies also pose challenges for the Church in Nigeria, as it needs to respond adequately to cases of sexual abuse perpetrated by Church personnel.

Given the reality of religious pluralism, the sociocultural differences between dioceses in the country, the continuous movement of people, and the need for uniformity in penal cases (Can. 1316), there is a need for research on the sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults that marries canon law with the socio-legal context of the Nigerian society. This is what this work does.

The book consists of six chapters with a total of 469 pages. First, the book examines the concept of a minor and a vulnerable adult in canon law and the three legal systems operating in Nigeria.

Second, it offers a conceptual definition of sexual abuse of a minor and a vulnerable adult. It identifies four factors that help categorise an act as sexual abuse: the victim must be a minor or a vulnerable adult, the absence of true consent, the act must be sexual, and constitute abuse. While the concept of a vulnerable adult is largely the same in the three legal systems operating in Nigeria, the concept of a minor differs in the three legal systems. The book also explores the forms (contact and non-contact), causes (interplay of risk factors), and effects (physical, psychosocial, economic, spiritual and Church’s pastoral life) of sexual abuse.

Third, as a sociological study, it highlights the incidence of sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults in Nigeria and identifies the peculiarities of Nigerian society that influence the phenomenon of sexual abuse in Nigeria—patriarchy, the status of the child, respect for elders, protection of family honour, fear of stigma, the threat to marriage, the Nigerian judiciary system, the disregard for the rule of law, the spirituality of forgiveness, the practice of spiritual cleansing, the breakdown of communal living, and the influence of the media.

Fourth, as a legal study, it explores the extant laws on sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults in customary, Islamic, and statutory laws (such as the Criminal Code, Lagos State Criminal Law, Penal Code, Child Rights Act, Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act, Cyber Crimes Act). It also outlines the stipulated penalties in the three legal systems and discusses the limitation of action for sexual abuse in Nigeria.

Fifth, as a canonical study, it traces the development of norms on sexual abuse from the Bible to the most recent statements by Pope Francis. It discusses essential documents on sexual abuse: Crimen Sollicitationis, Sacramentorum Sanctitatis Tutela, As a Loving Mother, and Vos Estis Lux Mundi. It also presents an exegetical study on the canonical delict of sexual abuse, exploring sexual abuse as a more grave delict, the victims of sexual abuse, the active subjects of sexual abuse, the various competent authorities to handle cases of sexual abuse, the prescription for the delict, and the canonical punishments for offenders.

Since Nigeria is a mission territory under the Dicastery for Evangelisation, the competent authority to deal with abuse cases sometimes differs from countries under the Dicastery for Bishops. Hence, this book outlines in a table form a detailed list of all the possible Church personnel perpetrators, the competent ecclesiastical authority to receive such reports in Nigeria, and the competent authority to judge the offence (Confer pages 293-297). This table is a vademecum for all ecclesiastical personnel in Nigeria and is essential for diocesan policy manuals.

Sixth, the work contains an analysis of the Church in Nigeria at the service of victims based on my fieldwork in all the 57 (arch) dioceses in Nigeria, including the Maronite eparchy in Ibadan (as of 2021). The section summarises all the teachings of the Catholic Bishops Conference of Nigeria on sexual abuse. It also includes a summary of the efforts of dioceses to attend to victims, proposals for preventing sexual abuse and dealing with cases reported, including the claim for damages. Seventh, as a priest, I know that there are false accusations. Hence, the book dedicates a section to falsely accused priests and how to manage the situation.

Finally, a book on sexual abuse in the Church will not be complete without a penal process. Hence, the work dedicates the final chapter to the penal canonical procedure to help readers know what is involved in judging cases of sexual abuse. Considering the Nigerian situation, it discusses the socio-legal context that could guide the competent ecclesiastical authority in imposing canonical penalties on guilty Church personnel in Nigeria.

I sincerely thank all those who assisted me in this work, especially the priests and religious from all the (arch) dioceses in the country who provided me with information about their (arch) diocesan policies and activities regarding safeguarding minors and vulnerable adults. I am now a formator and lecturer at Seat of Wisdom Seminary, Owerri. In order to continue promoting the safeguarding of minors and vulnerable adults in the Church in Nigeria, my book is freely accessible to all. Attached is the link to the free ebook.

The Church in Nigeria at the Service of Victims of Sexual Abuse.pdf – Google Drive

However, anyone interested in a hard copy can always order it from the Amazon store of your location (such as com, co.uk, it, de, fr, es, ca).

May God continue to help us🙏🏾

K’ọdị🙋🏾♂️